Fun With Stress 2.2

Work and Recovery Modes

Reading time: 6 minutes

While asleep we recover from the activities we’ve done, and prepare for the new day. Sleeping baby: newarta. Hay carrying women: mnspictures. Edit: Erik Stout

What happens in our body when we’re in work- or recovery-mode? How are those modes related to our availability and levels of energy? And what happens with them in the case of chronic stress? Let’s dive into it.

Roughly speaking we are in work-mode when we’re awake, and in recovery-mode when we’re asleep. While awake, we’re usually busy with a particular task or activity, for which we need conscious brain activity in order to think, and muscular activity for movement. By contrast, while asleep we don’t need to consciously think or move. And even though certain parts of our body related to recovery processes are active when we’re asleep, we shall see that the recovery-mode actually produces energy, while in the work-mode we are mostly consuming energy.

The principle we see here is one of nature’s most characteristic traits: its maintenance of equilibrium between the opposing forces of yang and yin. We see this in all cyclic phenomena such as day and night, the tides, sunshine and rain, the cycle of the seasons; and in our bodies we experience it for instance in our cycles of waking and sleeping or breathing in and breathing out. There is a constant push-and-pull going on between opposing forces as we adapt and readjust ourselves to the changing internal and external environments.

Winter and summer as an example of the cyclic nature of life. Image: fszalai

Our physiological equilibrium is called homeostasis. Homeostasis works a bit like a sophisticated thermostat that maintains temperature within set limits: if the room gets too cold, it turns on the heat; if it gets too hot, it turns on the air conditioner. Homeostasis in the human body works the same way, maintaining the state of internal equilibrium regarding body temperature, blood sugar levels, blood pressure, nutrient concentration, oxygen & carbon dioxide levels, etc.

Now, a stressor can be defined as anything in the outside world that disrupts the homeostatic balance, which is to say, anything or anyone capable of pushing our buttons. Consider our predicament in the previous chapter; being trapped in a pileup while the car in front of us is about to explode. This surely pushes our buttons and takes us out of homeostatic balance. The stress response is activated in order to survive, and is under those circumstances highly adaptive and beneficial, because, as we saw, it enabled us to slam the car door open and run towards safety.

The stress response therefore enables us with hyper focus and a boatload of energy so that we can work our way out of a sticky situation by means of almost super-human strength.[1] Hence when our buttons are pushed, we’re definitely high-up in the work-mode because a stress response needs a lot of energy for processes such as: diverting fuel from storage sites throughout the body to the designated muscles; increasing our heart rate, blood pressure and breathing rhythm (to get fuel and oxygen to those muscles as soon as possible); and making our brain hyper alert. And to make sure all available energy goes to our brain and skeletal muscles at that particular moment, the stress response temporarily shuts down long term energy consuming processes like cell growth, reproduction, and, most notably, digestion; more about that later.

After we’ve made it to safety, our body needs to regain the homeostatic balance which had been disrupted once we found ourselves in an acute life threatening situation. The fuel that we consumed needs to be replenished. Heart rate, blood pressure and breathing rhythm need to come down to their homeostatic values, and our muscles need time to relax and de-contract from their phenomenal exertion; because they had to perform on full force without so much as a warming up. In us humans, the optimal state for the restoration of homeostatic balance is characterized by both physical and conscious mental inactivity. For most of us, this is mainly while we sleep.

Quality of sleep can be assessed by how energetic we wake up afterwards. Image: PublicDomainPictures

One of the main characteristics of sleep is that it refuels our internal fuel tank and restores our energy supply, particularly to our brain. Because even though the brain constitutes about 3% of our total body weight, it uses about 20% - 25% of our total energy supply. Sleep is therefore a perfect energy-restorer since no energy is needed for conscious thinking processes or (the orchestration of) body movements.[2]

Yet fuel must first be produced before it can be restored, which is being done by our digestive system. There the food we eat is being processed into nutrients, vitamins, and fuel, which is our energy, and we are so programmed that our digestion is most active when we as humans are most passive, which is, again, particularly when we sleep. In normal circumstances, during our night’s sleep energy is being restored, and we wake up energetic in the morning.

When it comes to our levels and availability of energy, again we see how the interplay of two opposites – awake and in work-mode versus asleep and in recovery-mode – are both necessary to keep us healthy and fit. While awake we use conscious thinking and bodily movements to keep us focused on all our daily tasks, activities, and dealing with a stressor here and there; we consume energy to do so and hence we’re in the work-mode. While asleep, which is characterized by the absence of conscious thinking and bodily movements, our digestive system produces new fuel and restores our energy supply in the recovery-mode.

Sofar, so good. But what happens to our energy supply when stress becomes chronic, when our buttons are recurrently being pushed, on a daily basis, for months or even years on end? The short answer is: we’re being drained of energy.

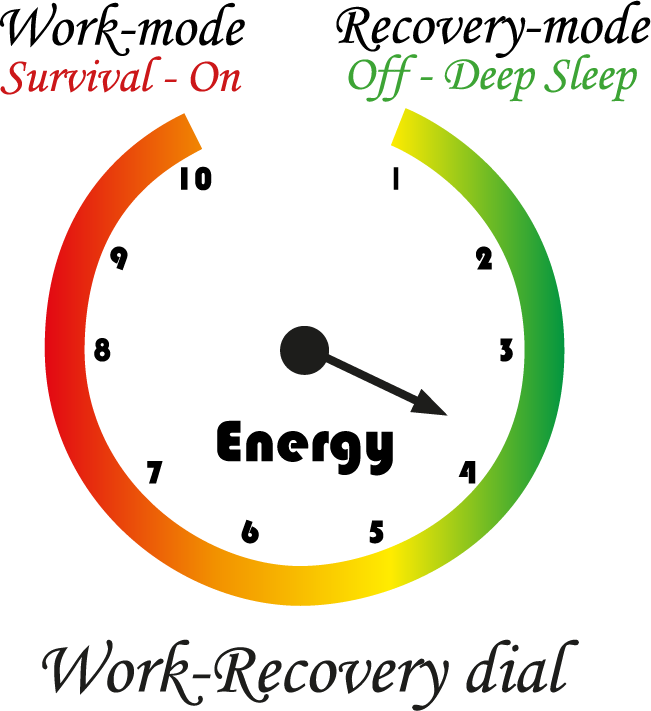

Imagine a speedometer that goes from 1 to 10, only instead of speed we’re measuring how far we are in work- or recovery-mode: a work-recovery dial. On 1 we’re in deep sleep, the ultimate recovery mode. On 10 we’re convinced that we’re in a life-threatening situation and therefore on hyper-alert, the ultimate work-mode. Furthermore, on 1 plenty of fuel is being produced while hardly any is being consumed, yet on 10 we need high amounts of fuel while none is being produced. Moreover, roughly from 1 to 4 more fuel is produced than consumed, and from 5 on upwards more fuel is consumed than new fuel is produced. And finally, during a stress response the work-recovery dial is on average between 8 and 10.

Levels, availability, production and consumption of energy can be assessed with the work-recovery dial. Image: Erik Stout.

Chronic stress points towards being in hyper alert mode for the better part of every 24-hour cycle. Without being aware, we’re being switched ‘on’ more and more until we forget how it feels to be switched ‘off’ and how to relax. Every time our buttons are pushed, the subsequent stress response needs a lot of energy while preventing energy production because it shuts off our digestive system. That means every new day we need more energy to provide for all them stress responses on top of our normal daily functioning, while every day less and less fuel is produced.[3] At some point there is simply no more fuel left in the tank, and when that point is reached there is a big chance of an almost complete systems shut-down. In popular terms, that is called a burn-out.[4]

Before we reach the point of burn-out however, we experience many low-on-energy-signs and signals indicating that we might be experiencing chronic stress, like: tiredness, aches and pains, broken sleep, or a foul mood, to name a few. These are the body’s way of raising awareness to the fact that one or more stressors are continuously pushing our buttons, keeping us in an incessant recurring stress response which is now beginning to permanently disturb our homeostatic balance.

Now, human beings are extremely adaptable. We can withstand extreme biological and psychological conditions. But if that goes on for too long, as in casu chronic stress, both our bodies and minds are going to have to make choices as to which functions will be sustained, and which ones will be let go, for example losing the ability to swallow.[5] Say goodbye to homeostatic, or any kind of balance for that matter, and hello to increasing frustration and fatigue.

Thus if our digestive system cannot fulfil its power plant function anymore and we’re being depleted of energy, pretty soon the rest of us are going to notice that as well. Therefore in the next chapter we’ll explore the workings of our digestive system under normal circumstances, when our buttons are pushed, and what can happen when that situation becomes the norm.

For now,

Jolly greetings,

Erik Stout

[1] Note that we work our way out of sticky situations, we don’t recover our way out of them – that comes after we’ve worked our way out. Timing is everything.

[2] Robert M. Sapolsky - Why Zebras Don’t Have Ulcers (chapter 11).

[3] Metaphorically speaking, we expect a car to keep driving the same amount of miles it usually does on a full tank, despite less and less fuel is being put in the tank with every refuelling.

[4] The term burn-out is actually adequately chosen because physiologically we work like a combustion engine. Therefore both oxygen and fuel are necessary for us to exist, and if all our fuel is burned up, well, you get the point.

[5] During my work as a physiotherapist I met a young lady whose swallowing reflex was disabled for almost half a year. Due to the continuous stress response more and more fuel was needed every day while less and less was produced by the power plant, causing a normal body reflex to cease functioning.

Will you help to keep this article up-to-date?

Dear reader, since we’re all human beings and therefore far from flawless, it’s always possible that the information in this article has become outdated or proven false. If you are aware of this, we’d be much obliged if you’d share that information by leaving a message underneath this article or via the contact form. After verification we’ll update the article immediately. Thank you so much in advance.