Five Questions: A Method for Journaling

Trauma Healing Without Judgment, Analysis, or Explanation

Reading time: 9 minutes

The best way to get to know yourself is to put the spotlight on yourself. Illustration: CCD20

‘Getting to know yourself’ means consciously connecting with your subconscious.

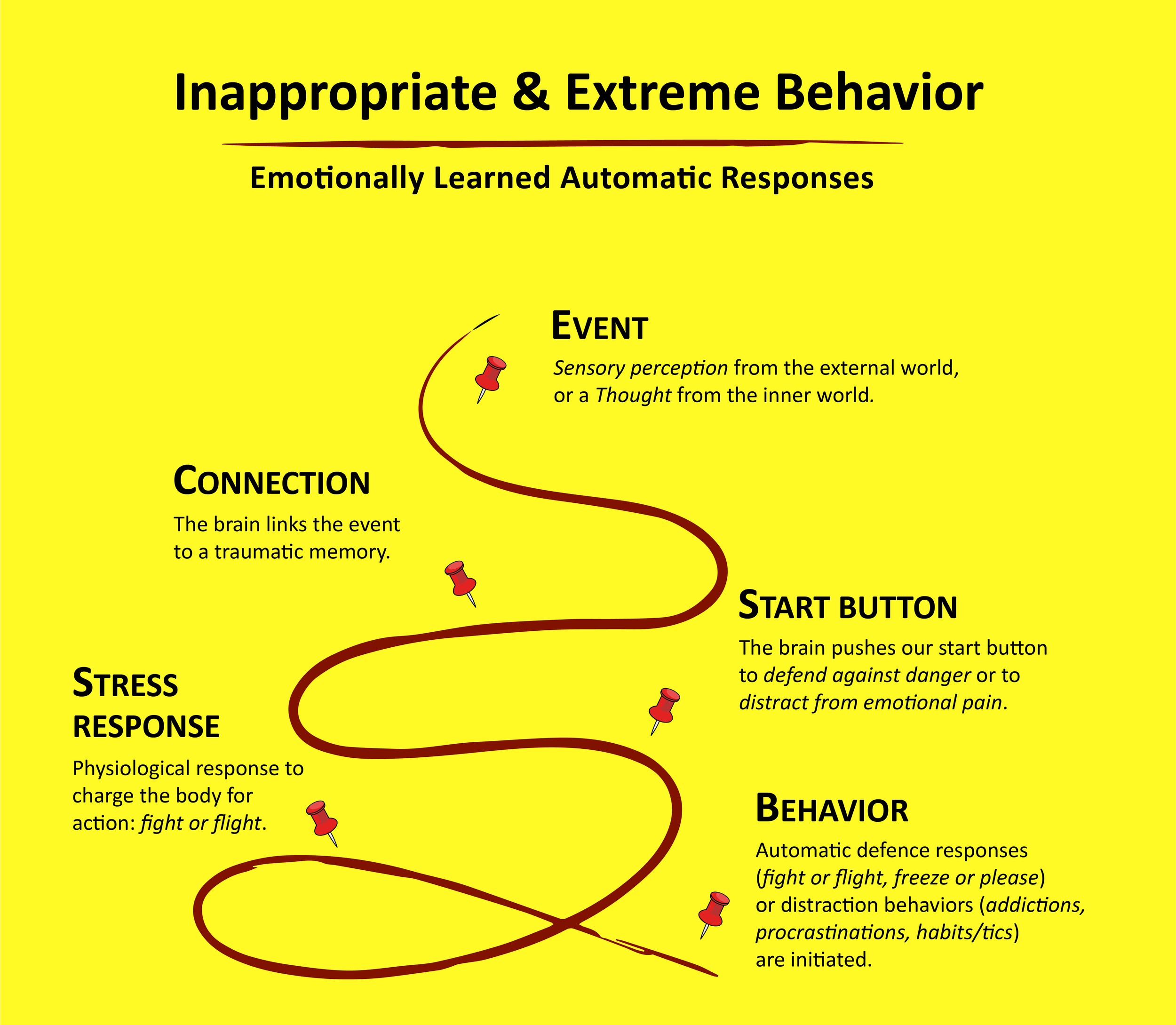

Our need for self-awareness often arises when we realize that our - usually automatic and involuntary - reactions to perceived danger or emotional pain no longer serve us. In other words, the behavior we display when our buttons are pushed leads us increasingly into conflict situations.

What we're talking about here are emotionally learned patterns: behavioral patterns we learned, particularly during childhood, as defense against danger or distraction from emotional pain (sometimes also physical pain).

The defense mechanisms are known as flight or fight. These mechanisms are triggered when our buttons are pushed and our brain perceives danger ahead. That initiates the physiological stress response which provides the necessary alertness and muscle strength to effectively flee, fight, or both.

In acute, life-threatening danger, such as a soldier unexpectedly standing face to face with an enemy, the stress response causes hypervigilance and releases large amounts of energy within the body. First there’s rapid assessment whether or not there is an escape route, after which the available energy is channeled to the leg muscles to flee, or to the upper body and arms muscles to fight.

In such situations, we are usually unaware of these processes and the associated bodily sensations. However, this changes radically as soon as our stress response is triggered without any immediate life-threatening danger, i.e. in emotionally dangerous situations.

Emotional danger refers to events that do not pose an immediate threat to life, but that trigger traumatic memories. This could be an image, smell, feel, taste, or sound, that reminds our brain of a previous situation in which we in fact were in danger - especially if such a situation occurred frequently over a long period of time. Examples of such situations are physical, emotional, and/or sexual violence, neglect, or parents who were physically and/or emotionally unavailable for their children. In such cases, we generally have four defense mechanisms at our disposal: fight, flight, freeze, and please.

These defense mechanisms all have a chance to develop equally effective in a loving and emotionally stable household. An effective fight response allows us to assertively set and protect our boundaries. An effective flight response allows us to withdraw when confrontation would actually increase the danger. Effective freezing means we stop struggling when further activity or resistance is pointless or counterproductive. And effective pleasing allows us to listen, help, and compromise just as effectively as we express and defend our own needs, boundaries, and perspectives.

However, most people only have access to one (or at most two) of the four defense mechanisms, because emotional stability within households is often lacking. An overdeveloped defense mechanism comes at the expense of (the development of) the others. So, when an event triggers a traumatic memory, which pushes our buttons and sets off the physiological stress response, the overdeveloped defense mechanism becomes our automatic - or default - response.

Moreover, overdeveloped defense mechanisms tend to escalate into inappropriate or extreme behavior. An overdeveloped fight response can escalate into narcissistic disorders. An overdeveloped flight instinct can escalate into obsessive, compulsive behavior, and perfectionism. An overdeveloped freeze response can escalate into dissociation, and an overdeveloped please response often leads to attachment issues and codependency.

As soon as perceived danger pushes their buttons, fighters and pleasers will try to control others in their usual ways. Fighters will typically use bullying, intimidation, or other physical and/or mental violence to control others. Pleasers, on the other hand, will do everything they can to please others, while losing sight of their own boundaries and needs.

Fleeters and freezers are more likely to avoid others as soon as perceived danger pushes their buttons. Fleeters try to control the situation by manipulating, changing, or leaving the perceived unsafe environment, while freezers tend to ‘disappear’ from the body (e.g., through daydreaming).

These behaviors, especially when one is unaware of them, often create a toxic environment and frequently influence the development of mental and physical disorders.

The four defense mechanisms (clockwise): fight, flight, please, freeze.

In contrast to our defense mechanisms, we often find our automatic distraction mechanisms (a.k.a. coping) in our addictions, habits, and procrastinating behaviours. These behaviors are aimed at alleviating emotional pain.

Emotional pain typically arises when a thought triggers a traumatic memory. Unlike emotional danger, which is usually perceived in our external world through our senses, emotional pain comes from within. Moreover, it is often accompanied with thoughs of self-blame, self-pity, or self-hatred.

These all manifest themselves in our body as bodily sensations that we’ve labelled unpleasant, undesirable, or uncomfortable. Therefore, since emotional pain actually manifests as bodily discomfort, it’s exactly those bodily sensations that we wish to distract ourselves from (i.e. medicate).

It is therefore no wonder that usual distracting behaviors like for instance smoking, alcohol, various drugs, gambling, social media, sex/pornography, food, or work, have such an appealling effect when we suffer from emotional pain.[1] They give instant gratification by means of bodily sensations that we have labeled pleasant and comfortable. However, that does not help any bit in processing the traumatic memory that caused our distracting behavior to emerge in the first place. On the contrary, every time we distract ourselves from an arisen emotional pain, the traumatic memory will return with more force the next time our brain is being reminded of that particular traumatic memory.

My journals from 2017 to 2023. Image: author.

The Method

Answer the questions a few hours or a day after you have fallen into a known and automatic defense or distraction mechanism. The intensity of the moment will then have subsided, allowing you to answer the questions objectively with healthy detachment (and without judgment). Record your answers in your journal, noting the date and location where you wrote them.

Then also make time to review your notes, for example by rereading your last entry before writing a new one. By reviewing your own thoughts, feelings, and behavior during and after your buttons were pushed, you are actually training the art of accepting yourself.

When examining emotionally learned patterns, it is important to avoid judging, explaining, and analyzing, which are functions of our cognition (the ability to think logically). Emotionally learned patterns are deeply anchored in our body memory (ie. bodliy sensations). No matter how hard we think about them, how many techniques, tactics, or cognitive methods we apply to them; as long as the patterns are not approached on an emotional level, that is, on a feeling level, they will not change.

Connecting with our emotionally learned patterns, which reside in our subconscious and can thus be considered part of our shadow side, is most effective through recognition, acknowledgement, and embrace (i.e. acceptance). This method is precisely aimed at recognizing, without judgment, explanation, or analysis:

which people and/or circumstances can trigger traumatic memories;

which thought and behavior patterns emerge in these situations;

where we feel these patterns in our body;

which bodily sensations we experience.

It's purely about observation.

Moreover, in this way you’re effectively processing traumatic memories without confronting them head on.

Try this method for at least one month before deciding whether or not it benefits you.

The Questions

What happened that pushed my buttons?

What came up in my mind?

a: Where did I feel the stress response in my body?

b: What bodily sensations did I feel there?What was the underlying emotion?

What did I do after my buttons were pushed?

1. What happened that pushed my buttons?

(In other words: Which sensory perception (image, sound, smell, etc.) or thought triggered a traumatic memory that pushed my buttons and triggered my stress response?)

There is a specific sequence in which our emotionally learned patterns become visible:

Event: our brain picks up on a specific image, sound, smell, taste, feeling, or thought.

Connection: our brain connects the event to a traumatic memory. Often, this is something someone says, does, or wears, but it can also be triggered by certain places or situations;

Start Button: our brain pushes our start button. This triggers our physiological stress response as defence against danger or distraction from emotional pain. At such a moment, we are often overwhelmed by: anger, fear, sadness, disgust, or ecstasy;

Stress Response: A physiological response to prime the body for physical action (fight or flight response);

Behaviour: The automatic and overdeveloped defense mechanism (fight, flight, freeze, or please) or distraction mechanism (addictions, habits, procratination) kicks in which manifests itself in our behavior.

We are often not aware of the sensory information (images, sounds, smells, etc.) or thoughts that our brain links to traumatic memories. That is why it is useful to investigate with whom, in which places, or in what kind of situations, we tend to relapse into our emotionally learned patterns. Once we gain insight into this, we can make increasingly better choices in the future about which kind of people, places, and situations are healthy and nourishing for us, and which ones we should avoid.

You immediately see that the information you gain from this question holds the potential for breaking your patterns. With little self-knowledge, we run the risk of repeatedly seeking out people and circumstances that evoke precisely those images, sounds, smells, etc., that our brain links to traumatic memories. By choosing different (kinds of) people, places, and situations in the future, we offer ourselves the opportunity to break out of the same cycle we're constantly running; the memory no longer keeps us ‘trapped’ in compulsively returning to familiar, yet toxic, environments. This is an important step towards emotional maturity and healing.

However, be aware that once we discover a pattern within ourselves, it doesn't mean we've immediately broken it. However, we will become increasingly aware of it in the future once we've reentered the pattern. Once we acknowledge the pattern, we essentially embrace it, effectively processing the trauma to which the memory is linked. This shortens the period during which we are ‘trapped’ by the traumatic memory.

Illustration: author.

2. What came up in my mind?

(Words? Sentences? Images? Evil wishes towards myself or others? Write everything down sincerely; nothing is right or wrong.)

Again, this is pure observation. As far as you can remember, write down everything that was going on in your mind while going through the emotionally learned pattern. Avoid judgments, explanations, and analysis; stick to the facts.

Emotionally learned patterns can harbour destructive fantasies such as the desire to hurt or kill someone. According to renowned psychiatrist and psychologist Carl Jung, this isn't a problem. In fact, it's a completely human reaction to an unwanted situation you can't control. It's your way of letting off steam without getting into trouble, though it's important to realize that such fantasies shouldn't be acted upon.

There's nothing in your mind to be ashamed of; not a single fantasy, word, sentence, or image. If you do feel ashamed of certain thoughts, write those down especially. One of the intended results of this method is to develop more compassion for yourself. You can achieve this, among other things, by acknowledging and embracing that there are thoughts you are ashamed of.

Once you've written down such mind contents, you can read them back. Instead of suppressing them, you can embrace them and decide to consciously love them. This creates a temporary antidote to shame, and if you do this often enough, the power of that shame will gradually diminish.

Moreover, you'll see that certain thoughts are linked to certain buttons and therefore to certain people and places. You'll gain insight into your thought patterns, and discovering their compulsive nature can be truly liberating.

What came up in your mind after your buttons were pushed? Image: Pablochavesuy

3a. Where did I feel the stress response in my body?

Our body is constantly changing.[2] We can feel the continuous movement and transformation processes that take place in our body as bodily sensations.[3] As a rule, however, we notice little or nothing of these changes because we have learned to direct our attention primarily outside of ourselves. In doing so, we have also learned to ignore all the subtle signals the body gives all the time that we are pushing ourselves beyond our limits. Only when severe physical pain or serious illnesses manifest themselves do we focus our attention on our own body. Yet then it is often too late to prevent permanent damage.

By exploring, without judgment, where in our bodies we can feel a stress response, we can lovingly reconnect with it. This helps us to more quickly sense the subtle signals our body is giving us, allowing us to adjust our course, because we now know we're overexerting ourselves.

Moreover, locating the stress response in your body helps you distinguish between different emotions. As mentioned, we're often no longer aware of which sensory information our brain links to traumatic memories. So, you might suddenly find yourself in an automatic defense or distraction behavior without understanding where that came from.

By examining where in the body the stress response is felt, we discover that different emotions often manifest in different locations. Being able to distinguish between an outburst of anger or grief can be helpful in recognizing the event that ultimately triggered a stress response with its subsequent emotionally learned pattern.

Therefore, after have fallen into an emotionally learned pattern, always write down where in your body you clearly felt that.[4] This will give you an increasingly clearer picture of which people, places and situations can push your anger, fear, grief, or ecstatic buttons.

3b. What bodily sensations did I feel there?

Physiological adjustments during a stress response that are usually easily felt include the faster and harder beating of our heart, faster breathing, and contraction of our skeletal muscles. This can sometimes feel like palpitations, hyperventilation, muscle aches, or muscle cramps.

However, if it's unclear that our buttons were pushed, fear can arise that something is wrong with our heart or lungs—a fear that can be exacerbated when medical tests show that ‘nothing is wrong with them.’ Gaining insight into the fact that a stress response is causing the symptoms can, paradoxically, have a calming effect; because at least you now know the cause.

The clearly noticeable bodily sensations that occur after a stress response are different for everyone, but mostly the stress response is felt somewhere in our torso or head. This can range from pain and cramps in the pelvic area, stomach or intestinal cramps, a stone in the stomach, a backache, a tight band around the abdomen, pressure on the chest, a strong and rapid heartbeat (can feel like palpitations), the feeling of someone pulling our stomach out through the esophagus and mouth, difficulty in swallowing, nausea and/or dizziness, headaches or migraines, to difficulty in breathing (can feel like hyperventilation), to name just a few. However, the combination of bodily sensations and locations in the body where the stress response can be felt is unique to each individual.

Other terms used to describe bodily sensations can be found under point [3].

Where did the stress response manifest itself in your body? Image: GDJ

4. What was the underlying emotion?

(One of the basic emotions: anxiety, anger, grief, disgust, or ecstasy.)

Nearly every word we use to express an emotional state is underlain by one of these basic emotions. It's worth noting that anger is a so-called secondary emotion, because anxiety is always the primary emotion underneath it. However, each has its own button that can be pushed, resulting in the inevitable physiological stress response, combined with its own unique set of tangible bodily sensations.

For example, if your research shows that during an outburst of anger, you feel your heart racing, a band tightening around your chest, and your face hardening into a mask, you'll notice that these bodily sensations repeat themselves each time your anger buttons are pushed.

It is particularly insightful to learn where the basic emotions express themselves in your body, especially when it is unclear which event triggered a traumatic memory and pushed your buttons. As soon as you feel very angry and experience the bodily sensations associated with anger, you know your buttons have been pushed. With that knowledge, you can look back and ask yourself: What event (who or what) triggered a traumatic memory that pushed my buttons? This will help you then to answer the first question of this method, which will increase your insight into your subconscious accordingly.

Which of the basic emotions underlies the stress response? Image: Mariakray, Edit: auteur

5. What did I do after my buttons were pushed?

(Describe your behaviour.)

Did I engage in a full frontal confrontation (e.g., with someone else, an authority, breaking things, etc.)?

Did I become obsessive about cleaning or tidying up; or did I otherwise try to excessively control my material environment?

Did I create a rigid separation between my body and mind to avoid experiencing pain?

Did I resort to extreme pleasing behavior?

Did I seek distraction (with a cigarette, a drink, social media, sex, work, gambling, etc.)?

Other behavior, namely: …

The main cause of the development of emotionally learned patterns can be found in the bodily sensations associated with a stress response. The vast majority of people experience these as a form of emotional pain. Since we have difficulty tolerating pain in general, it's quite possible that we automatically resort to our defense or distraction mechanisms.

Whatever behavior we exhibit, it's not uncommon for us to feel ashamed of that behavior. This is especially true when we feel to have no control over that behavior. But here too, there's much to learn and much to gain by observing ourselves.

By objectively and without judgment writing down what we did after our buttons were pushed, we can gain insight our unconscious and involuntary behavioral patterns. Here, too, discovering the compulsive nature of these behaviors can be liberating, because writing them down means acknowledging and beginning to embrace that compulsive behavior—in other words, accepting yourself.

Image: geralt

In summary, these questions hold the power to get to know your subconscious in a compassionate way. It's about observing your own thoughts, feelings, and behaviors from the outside, as it were, and only writing down factually what happened. Again, and I can't emphasize this enough: try not to judge, analyze, or explain.

Judgments are of little use in self-exploration anyway, and explanations will come naturally if you continue this method long enough—I'd say at least six months.[5]

However, if you start this method and find that it only meets with resistance, feel free to stop and look for a method that suits you better.

For questions and comments, please leave a message below this article or contact us via the contact form. Have fun and good luck with your explorations.

Jolly greetings,

Erik

Notes

[1] The biology, psychology, and sociology of addictive behavior are beautifully described by Dr. Gabor Maté in his book In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts.

[2] These changes manifest as movement and transformation. Our heart beats continuously, a constant flow of blood, lymph, and air moves through our bodies, and our metabolism also provides a great deal of movement. In addition, many substances are converted into other substances, such as oxygen into carbon dioxide and food into nutrients and vitamins.

[3] Example words that can be used to describe bodily sensations are: Hot, Warm, Cold, Cool, Heavy, Light, Hard, Soft, Itching, Tingling, Vibrations, Throbbing, Bursting, Cramps, Tension, Relaxation, Fading, Flowing, Stinging, Numbing, Pressure, Pain, Pulsations, Waves, Stretching, Nausea, Dizziness, Dry Mouth, Sweat.

[4] Head, Face, Neck, Arms, Hands, Chest, Abdomen, Lower Abdomen & Pelvis, Neck, Back, Lower Back, Buttocks & Hips, Legs, Feet.

[5] I've been using this method for nine years now.